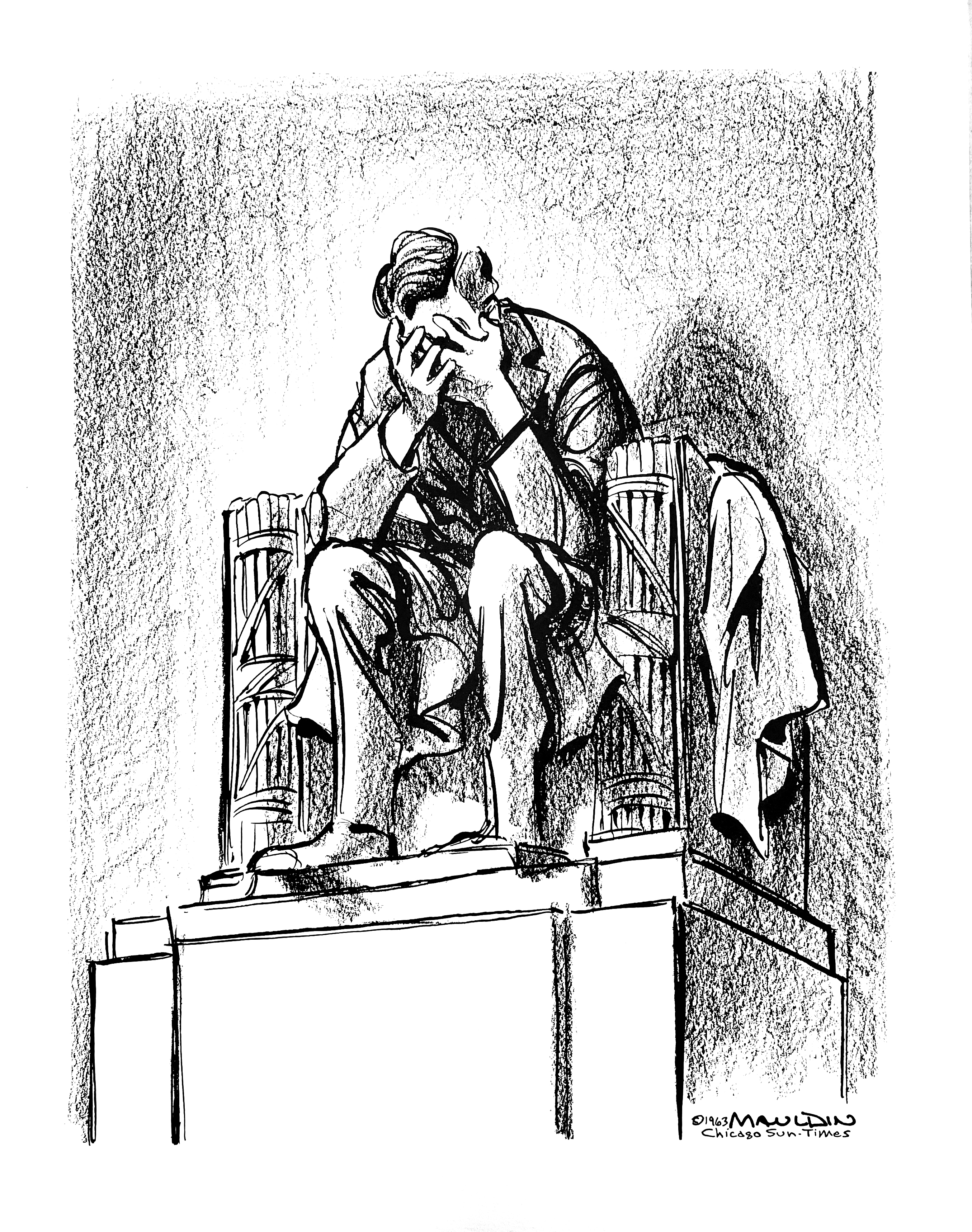

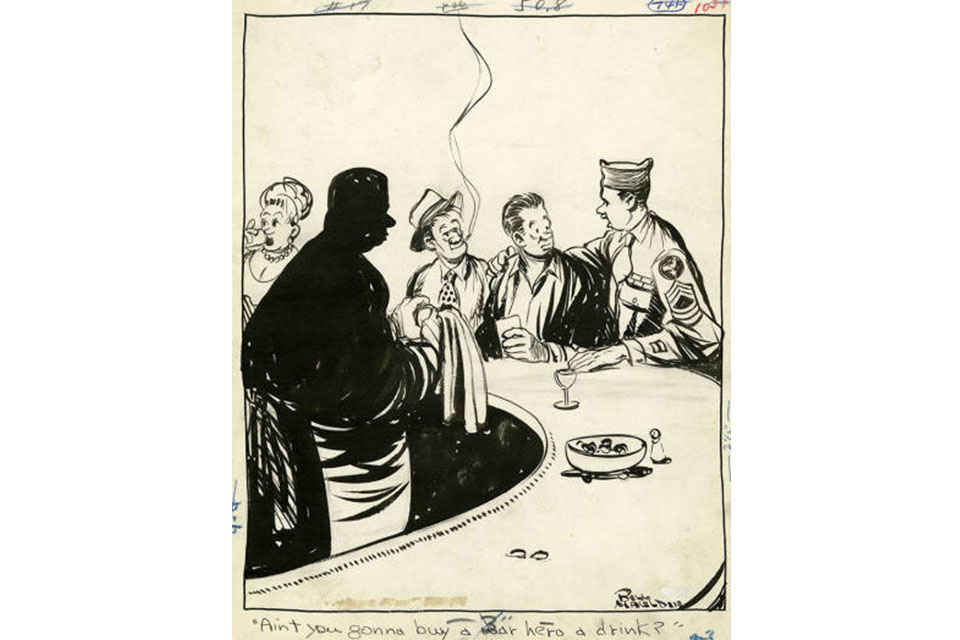

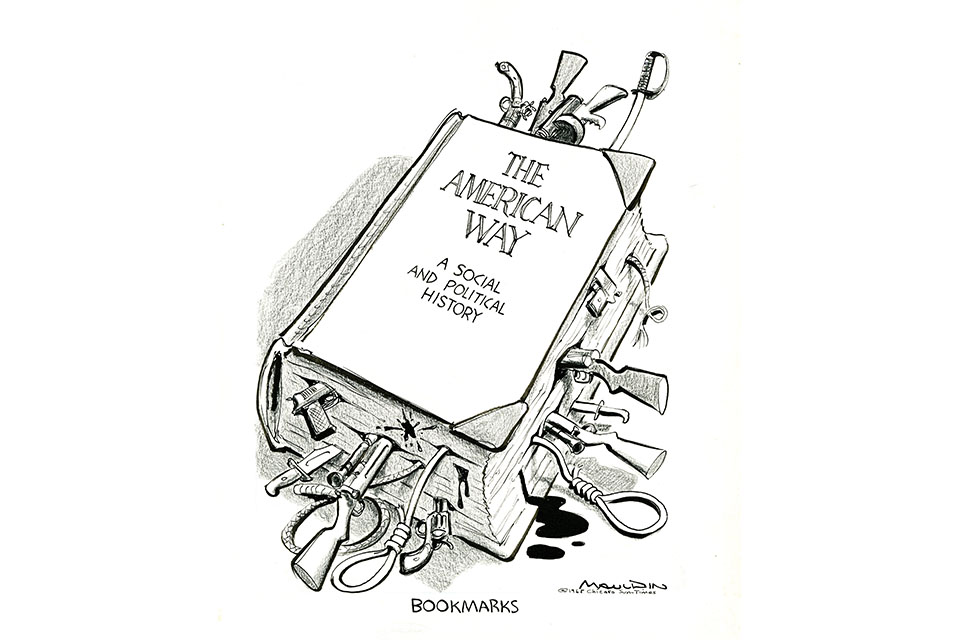

“Bill Mauldin’s wild fifty-year career defied F. Scott Fitzgerald’s oft-quoted remark about there being no second acts in American lives,” wrote Tom Brokaw in Drawing Fire: The Editorial Cartoons of Bill Mauldin. “Mauldin first catapulted to fame at age of twenty-two as the greatest cartoonist of the Second World War, delivering grim humor from the frontlines to newspaper readers back home. After the war, he stunned fans by using his syndicated cartoon as a bully pulpit to protest racial discrimination and anti-communist hysteria.”

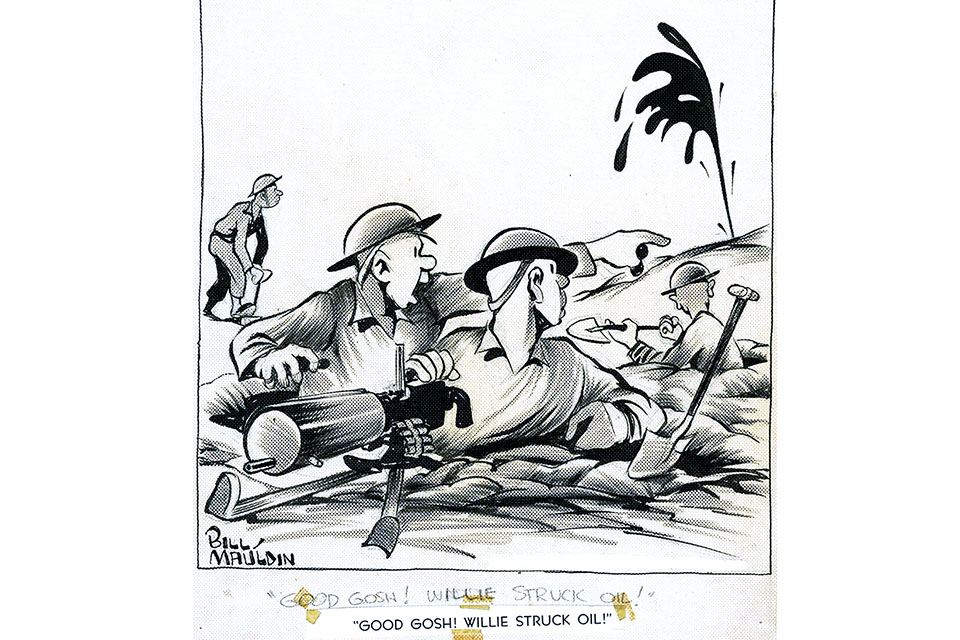

Mauldin, a sergeant in the 45th infantry division during World War II, understood that for many veterans the war did not end when they came home. The work of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Stars and Stripes cartoonist resonated so deeply with soldiers and veterans alike that his cartoon strip of two war-weary grunts “Willie & Joe” found wild popularity throughout the 20th century.

“You know, I had planned to kill Willie and Joe on the last day of the war,” Mauldin recalled to HistoryNet in 1989. “That’s the one thing every soldier dreads, getting killed on the last day. I wasn’t sure how I was going to do it. Most likely I would have had a shell land in their foxhole or had them cut down by a machine gun. I wouldn’t have drawn their corpses. I’d just have shown their gear with their names on it, or something like that.”

Drawing Fire, out now, draws from Mauldin’s decades-long cartoonist career and features 150 images selected from more than 4,500 Mauldin cartoons housed in Chicago’s Pritzker Military Museum & Library.

Edited by Mauldin’s biographer Todd DePastino, with a preface written by Tom Hanks, Drawing Fire includes the famed cartoonist’s wartime and political cartoons to kick off the museum’s celebration of what would have been Mauldin’s 100th birthday.

Unless otherwise noted, all images courtesy of the Pritzker Military Museum & Library. Captions from Drawing Fire: The Editorial Cartoons of Bill Mauldin.

[hr]

Thank you for visiting historynet.com. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a small commission.