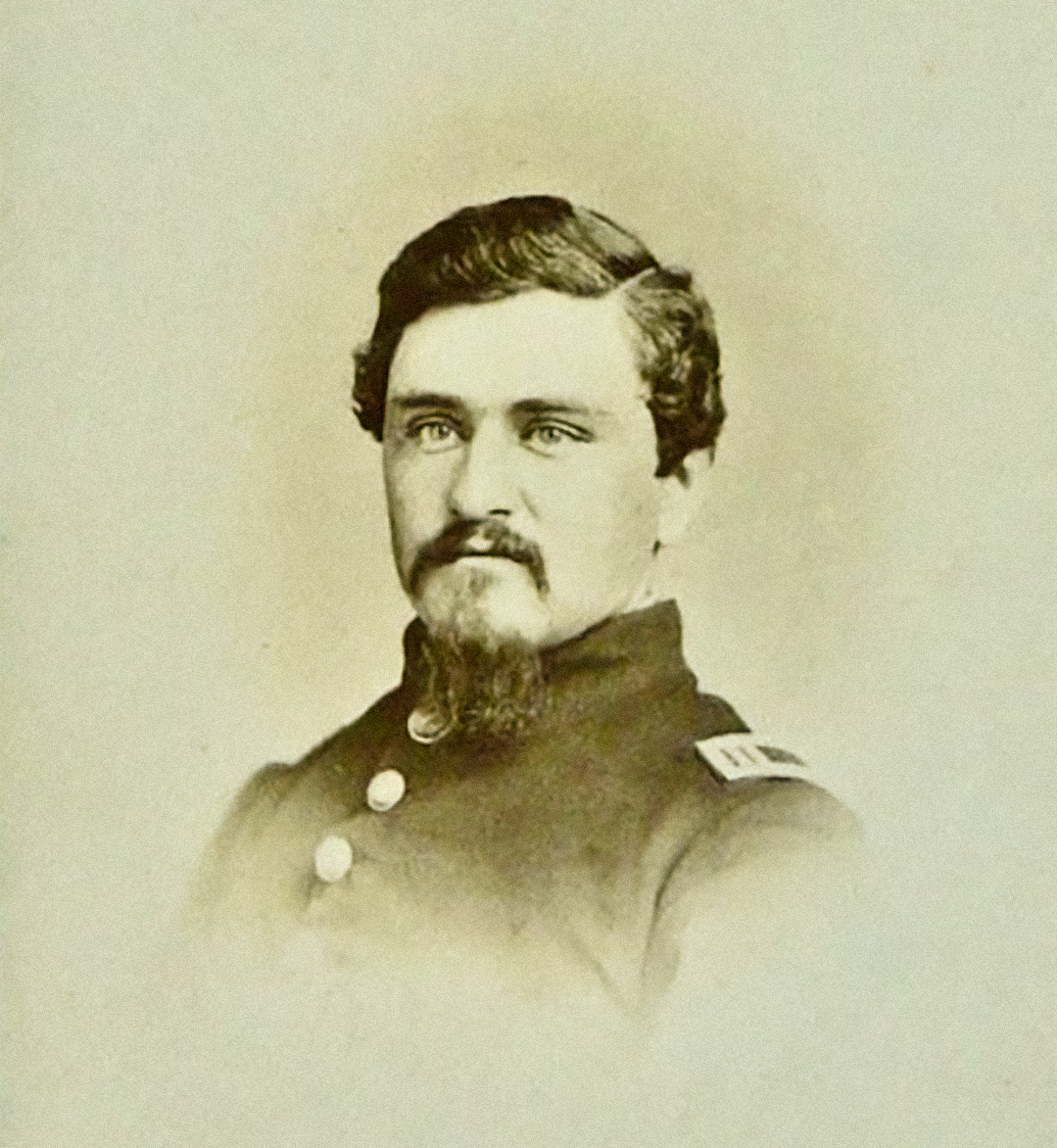

This letter was written by James Henry Platt, Jr., who was raised in Burlington, Vermont. He completed preparatory studies and graduated from the medical department of the University of Vermont at Burlington in 1859 when he was 23. On February 23, 1859, he married Sarah Caroline Foster in Rutland, Vermont. He later married the suffragist and widow Sarah Sophia Chase Decker, who survived him.

“Harry” (as he preferred to be called) enlisted in August 1861 as a Captain in Co. B, 4th Vermont Volunteers. The 4th Vermont was organized at Brattleboro under the young Colonel Edwin Henry Stoughton and spent its first autumn in Virginia with Brooks’ Brigade, primarily tasked with the defense of Washington, D.C., at Camp Griffin.

While at Camp Griffin, the 4th Vermont was brigaded with several other Vermont regiments and was, therefore, often referred to as the “Vermont Brigade.” The brigade had a storied career and played a part in many important battles of the Army of the Potomac, including the Peninsula Campaign, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Second Battle of Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, Petersburg, Fort Stevens and Winchester.

This incredible letter pertains to the first real test of the regiment which took place during McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign. After landing his troops on the tip of the peninsula formed by the James and York rivers, McClellan sent them towards Yorktown. Long before arriving there, however, he found that the Confederates had established a line of defense across the entire peninsula on or near the Warwick river — a formidable barrier by itself but also heavily fortified. On the morning of April 16, 1862, Brig. Gen. Baldy Smith sent two Vermont regiments from his 2nd Brigade towards the Confederate position near Lee’s Mill with orders to open fire on any working parties. Though the infantry opened the engagement, it devolved into an artillery duel with both sides suffering losses. No advance was accomplished and McClellan settled on the strategy of a siege. The engagement of April 16, 1862, has been referred to by various names, including the Battle of Lee’s Mill, the Battle of Burnt Chimneys, or the Battle of Dam No. 1.

Camp near Yorktown, Virginia

April 20th, 1862

My Darling Wife,

No fighting worth mentioning has occurred since yesterday when I last wrote you. About 3 p.m., the rebels displayed a “flag of truce” from their works, and proposed a cessation of hostilities for two hours to enable them to bury their dead. This was agreed to on our part on condition that they send us the dead of our regiments left on their side of the creek on Wednesday. The preliminaries being arranged, the sad work commenced and a party of their men brought our dead, one by one, half-way across the dam at which point they were received by our men. The spectacle—though melancholy—was deeply interesting. The rebel troops were in full sight, all portions of their works being covered with them, and a large body of their horsemen were stationed along the bank of the creek. Our men were also out in large numbers. On the dam midway between the two shores were two rebel officers and two of Gen. Smith’s staff amiably conversing. To have seen them meet, one would have thought it a meeting of dear friends long separated so cordial were the handshakes & so mutual the smiles.

“They expressed their determination to make every farm in Virginia a graveyard and every house a hospital before they would yield…”Capt. Harry Platt, Co. B, 4th Vermont, 20 April 1862

A large party of the rebels were engaged sorting the dead, conveying their own into their fort, and ours to the party waiting to receive them. Thirty-three bodies were conveyed to our side, and seemingly three were carried into the fort to [every] one brought over [to ours]. While engaged in the work, the two parties conversed together freely. One of the rebels said he was from Burlington, Vermont, and his name he gave as Lyon. They expressed their determination to make every farm in Virginia a graveyard and every house a hospital before they would yield and other remarks of the “dying in the last ditch” style.

At the expiration of the two hours, forty minutes was agreed upon for both parties to place themselves in safety and at the end of forty minutes the white flag was hauled down and we were enemies once more. It was a sad sight to me to see my old friends and comrades from Co. F and some of the men in Co. K to whom last summer I taught the rudiments of military discipline, brought in lifeless & disfigured by wounds and lying so long on the field uncared for. But such is war. Gallantly they met the fate of true soldiers & fell bravely fighting for the noble cause we are defending.

It is a curious circumstance that rebels exhibit no flag. The white flag is the only emblem we have seen.

Our dead were buried carefully and tenderly amid the groups of sorrowing comrades who witnessed this last sad office.

I went out at 9 o’clock with a fatigue party of one hundred men to work on rifle pits & trenches which are being thrown up to shelter our men who protect the batteries. Imagine an open field of ten or twelve acres directly in front of the rebel fort with the creek between and surrounded on three sides by dense woods. Let me attempt a diagram which may better enable you to understand the position. You will find it enclosed & please don’t laugh at it as it’s only for your eyes. The rifle pits marked 10 are simply dry ditches with the dirt thrown up so that when a man is standing in the ditch, the embankment rises about a foot above his head thus completely protecting him from bullets. These, as you perceive, allow communication between the different batteries at all times & serve to protect infantry. We worked on these all night. Every few minutes the rebels would fire a heavy volley of musketry at us to embarrass us in the work. The men were all in the trenches shoveling like good fellows. I stood on the bank keeping a sharp look out for the first sign of a volley. The night was very dark & it rained hard all night. When the rebels fired, I could see the flash of the powder, then hear the report. At the flash, I would sign out “Down!” and jump into the trench and just get in when bang would come the bullets whizzing over our heads & striking all around us, when we would jump and work away until the next volley, & thus we passed the night.

The firing alarmed the camps and three times the regiments were called out by the long roll and marched out under arms so that on the whole, those of us who were at work had about the best of it. Tonight the entire regiment with the exception of those who were out last night are out as guards for the batteries. It has been raining all day but has stopped for the present.

I am very comfortably fixed and the regiment is encamped in a magnificent grove of great pines. I should enjoy myself very much could I only know that my dear wife was well and free from suffering. I do not hear at all regularly from you. Our mails come and go as it happens. We do not know whether our letters ever reach their destination but I continue to write to you almost daily. Believe me dear one, you are continually in my thoughts and your suffering causes me much anxiety and if I could only bear them for you or in some way lighten them, it would cause me great happiness. I look anxiously for the hoped for intelligence of your convalescence.

Ever your own loving, — Harry